It is well known that poor people tend to have kids who also grow up to be poor. Many people imagine that this relationship is causal such that if poor families were given more money in the past generations their contemporary descendants would have more money today. This view is commonly held both at the level of individuals and at the level of groups where it is often said that if some historical incident made a group poor in the past then that incident likely contributes to that groups poverty today. In this article I will argue that this view, at least when applied to a first world context, is contradicted by various lines of evidence and that genetics is a better explanation for why it is that poverty runs in families.

Adoption Studies

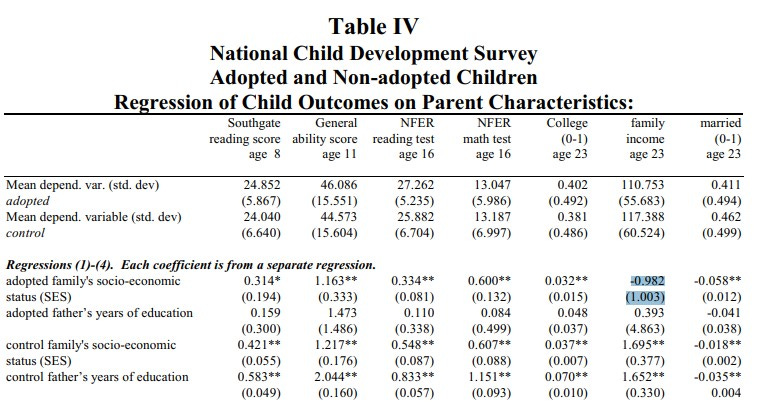

The most obvious way to see if the correlation between the economic status of parents and offspring results from genes or the environment is to look at adoption families. Sacerdote (2000) reports on the results of two such studies both of which found that parental income is not significantly related to offspring income in adoptive samples.

(Notably, there were features of the adoptive home environment, for instance maternal education, which did predict offspring income. But parental income was not such a variable.)

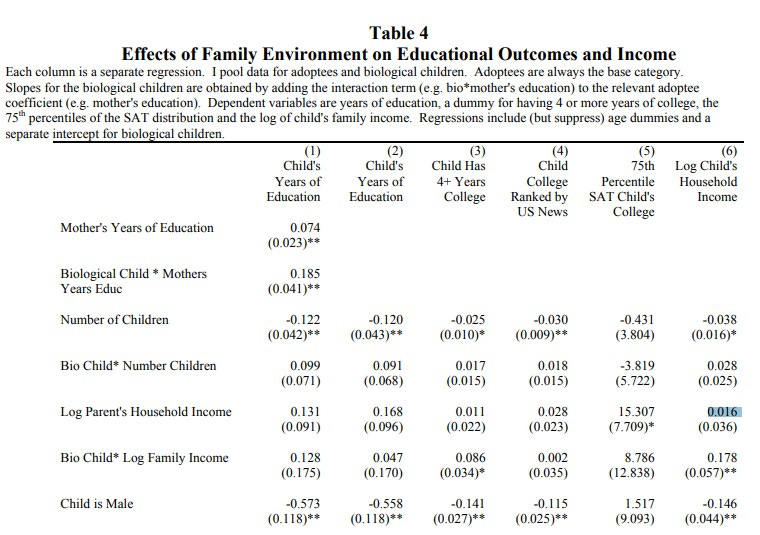

Sacerdote (2004) reports on a third study which found that a person’s adoptive family income fails to correlate with their own income while their biological families income correlates with offspring income at 0.178 despite these kids being raised in a separate home.

Thus, adoption studies are one line of evidence supporting the view that the direct transmission of income between parents and offspring is due to genetics.

Random Shock Studies

Another line of evidence involves so called “random shocks” or changes to parental economic status which are plausibly random with respect to parental genetics, personality, etc. There are several such studies done on data from 19th century America and they uniformly support the contention that, in the long run, such random shocks have no impact on family economic status.

For instance, Bleakley et al. (2016) report that: “We track descendants of participants in Georgia’s Cherokee Land Lottery of 1832, in which nearly every adult white male in Georgia took part. Winners received close to the median level of wealth – a large financial windfall orthogonal to participants’ underlying characteristics that might have also affected their children’s human capital. Although winners had slightly more children than non-winners, they did not send them to school more. Sons of winners have no better adult outcomes (wealth, income, literacy) than the sons of non-winners”

Similarly, Ager et al. (2021) reports that: “We document that White Southern households that owned more slaves in 1860 lost substantially more wealth by 1870, relative to Southern households that had been equally wealthy before the war. Yet, their sons almost entirely recovered from this wealth shock by 1900, and their grandsons completely converged by 1940.”

Another paper worth mentioning is Sacerdote (2005). This paper compares life outcomes for the children and grandchildren of enslaved and free black Americans. After controlling for the negative economic effects of living in the south post slavery, Sacerdote finds that these groups converged after 2 – 3 generations.

To be specific, the children of slaves were 8% less likely to be in school than the children of free blacks. For the grandchildren of slaves, there was no significant effect. Similarly, the gap in months of schooling between the grandchildren of slaves and free blacks was a statistically insignificant 0.3 months. Moreover, the income of children of slaves (estimated based on occupation) did not significantly differ from the income of children of free blacks. The descendants of slaves were 6% more likely to work in manual labor, but this was not statistically significant. Finally, Sacerdote finds that the rate of home ownership was 34% for the children of slaves and 32% for the children of free blacks.

Thus, research on random shocks suggest that large random changes to a person’s economic status will have no significant effect on the economic status of their grandchildren. This fact is very hard to explain on any conventional explanation of economic inequality.

Lottery Studies

Another relevant line of evidence concerns lottery winners. If poverty causes more poverty, it must do so through some mechanism. Normally the idea is that without money people are doomed to a low quality environment and lack the funds to invest in themselves. If this is so, then winning a moderate amount of free money, not enough to stop working, should improve people’s environment and ability to invest in themselves such that their earned income increases. This is not what the data shows.

Looking at a dataset on winners of the lottery in Massachusetts in the 1980s, Imbens et al. (2001) found the more unearned income that was won the more earned income decreased. The same has been found in analyses of lottery winners in Sweden (Cesarini et al., 2015). Comparing present lottery winners to future lottery winners, Golosov et al. (2021) found that "For an extra 100 dollars in wealth, households reduce their annual earnings by approximately 2.3”.

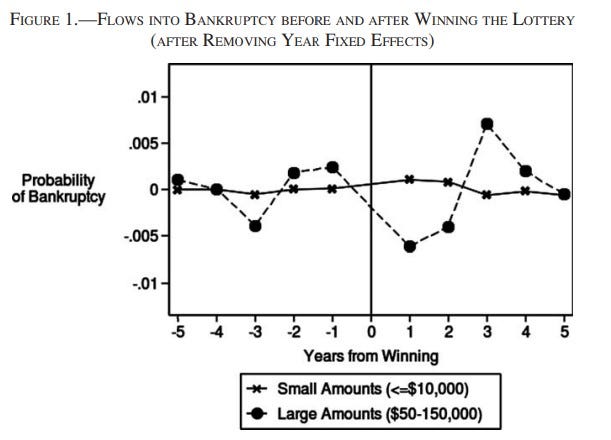

In fact, not only do lottery winners not improve their income, even their wealth is not impacted in a lasting way by lottery winnings. This is what is suggested by Hankins et al. (2011) who analyzed how the probability of bankruptcy varied by how much someone won in a Florida lottery. They found that small winnings had no impact on bankruptcy while large winnings predicted fewer bankruptcies in the first years following the win but more bankruptcies in the years after that such that there was no long run impact on the probability of bankruptcy.

Guaranteed Income Experiments

We might object to this on the grounds that lottery winnings are one time large payments and poor people would be better aided by regular smaller payments over a longer period of time.

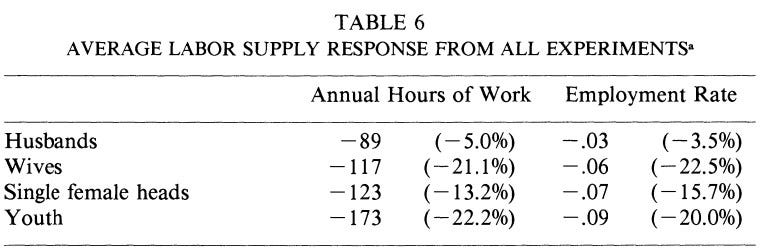

Such concerns have been addressed by the various experiments with guaranteed income that have been carried out in the first world. Robins (1985) combined data from several guaranteed income experiments done in the United States during the 1960's and 70s. Aggregated together, data from these experiments found that guaranteeing people's income at or above the poverty level decreased the amount of time they spent working and their earned incomes.

Robins also notes that the most generous of these experiments generated the largest reductions in economic productivity among recipients.

Price et al. (2018) looked at the effect that giving a family a guaranteed income for 3 - 5 years had on that family decades later. They found that this unearned income decreased long term earned income by about $1,800 per year for recipients and had no impact on the economic productivity of the recipients children. The paper also found that recipients responded to the unearned income by switching jobs into a less cognitively demanding occupation.

Gennitian et al. (2022) looked at a sample of 1,000 mothers who were randomized to get an unconditional cash transfer of either $333 or $20 each month for several years. The cash transfer was found to have no impact on the mother's earned income.

Thus, data from adoption studies, random shock events, lottery winnings, and guaranteed incomes, suggest that if poor families were given f money a century ago, or rich families were financially ruined a century ago, there would be little difference in who is poor and rich today.

The Case for Genes

We can now contrast this with the strength of evidence favoring genetics as an explanation. We’ve already seen that adoption studies show families resemble each other in income even when separated. Similarly, twin studies show that, in the United States, roughly 41% of the variation in income is explained by genes while only 9% is explained by the family home environment (Hytinnen et al., 2019). The necessary implication of this is that the vast majority of the correlation in income between parents and children is due to genes rather than the environment.

Further evidence of the genetic transmission of wealth comes from Clark (2021). The idea behind this paper is that if wealth is being transmitted purely due to genetics then how similar two relatives are in wealth will be a simple function of how genetically related they are.

Importantly, this model makes predictions which are hard to explain if the environment is playing any significant role. For instance, because people are as related to their 1st cousins as they are their great grandparents, this purely-genetic model predicts that people’s wealth will be equally correlated with the wealth of their cousins and great grandparents even though most people have spent time with their cousins and never met their great grandparents. It also predicts that the wealth correlation with great-great grandparents will be in between that of 1st and 2nd cousins and that, moreover, the wealth correlation between people and their second cousins will be equal to their correlation in wealth with their great-great-great grandparents.

Using data on 402,000 English individuals who lived between 1750 and 2010, it was shown that relatives similarity in wealth (and education and occupational status) basically perfectly aligned with the specific predictions of this genetic model. The odds of this pattern occurring if the environment was significantly involved is nearly zero.

To conclude, the evidence suggests that genetics explain all, or nearly all, of why it is that poverty runs in families, and a direct causal impact of poverty explains virtually nothing across more than two generations.

Sean will you please ensure that you YouTube channel is synchronized to Odysee?

İf income variations are explained by genetics, Why income-IQ correlation is only 0,3?